Whether you love a spot of art, history, nature or culture, you’re bound to find a museum for you in Reykjavik.

The Icelandic capital boasts a huge array of museums covering everything from whales to maritime history, manuscripts and photography.

There’s even a museum dedicated to phalluses, which bills itself as “the world’s only genuine penis museum”.

Regular readers of my blog will probably have guessed that I’m rather partial to a museum.

So it goes without saying I’d planned a visit to a trio of Reykjavik’s most illustrious institutions – the National Museum of Iceland, the National Gallery of Iceland and the Perlan Institute.

National Museum of Iceland

A short walk from Hljómskálagardur Park and Tjörnin Lake lies the National Museum of Iceland, which tells the story of Iceland’s history and culture.

The museum dates back to 1863, but it wasn’t given a permanent home until 1944 when Iceland was granted independence from Norway.

Situated inside a not-particularly-attractive grey concrete building that looks a bit like a 1980s council office block, the museum is set over three floors.

I started my visit at a small photography exhibition on the ground floor, which showcased images of everyday Icelandic life and landscapes.

I then made my way up the main staircase to ‘Making of a Nation: Icelandic Heritage and History’, an exhibition over two floors that makes up the bulk of the museum.

The first floor recounts the first few centuries of Iceland’s history, from its settlement around 870 to 1600.

It’s filled with interesting displays that cover various aspects of the country’s history and culture, including its conversion to Christianity, its early economy and its occupation by the Norwegians in the 1240s.

It’s very well curated and I found myself absorbed by the raft of information and objects on display.

My favourite artefact was the small bronze figure of a man (above), which is thought to either depict Thor holding a hammer or a man holding a Christian cross.

The cute figurine is around 1,000 years old and I was amazed it was still in such good condition.

The first floor was home to a few other small exhibits, including an area adorned with the portraits of Iceland’s most powerful families from centuries past, alongside a couple of lovely wooden chairs (above).

‘Conversing with Sigfus’, meanwhile, showcased the work of contemporary Icelandic photographer Einar Falur Ingólfsson who’d recreated the photos of Sigfús Eymundsson 150 years later.

Eymundsson was the first person to photograph Iceland’s tourist hot spots.

I liked the small, temporary exhibit, which runs until the end of December 2025, and was intrigued to see how the country had changed over time.

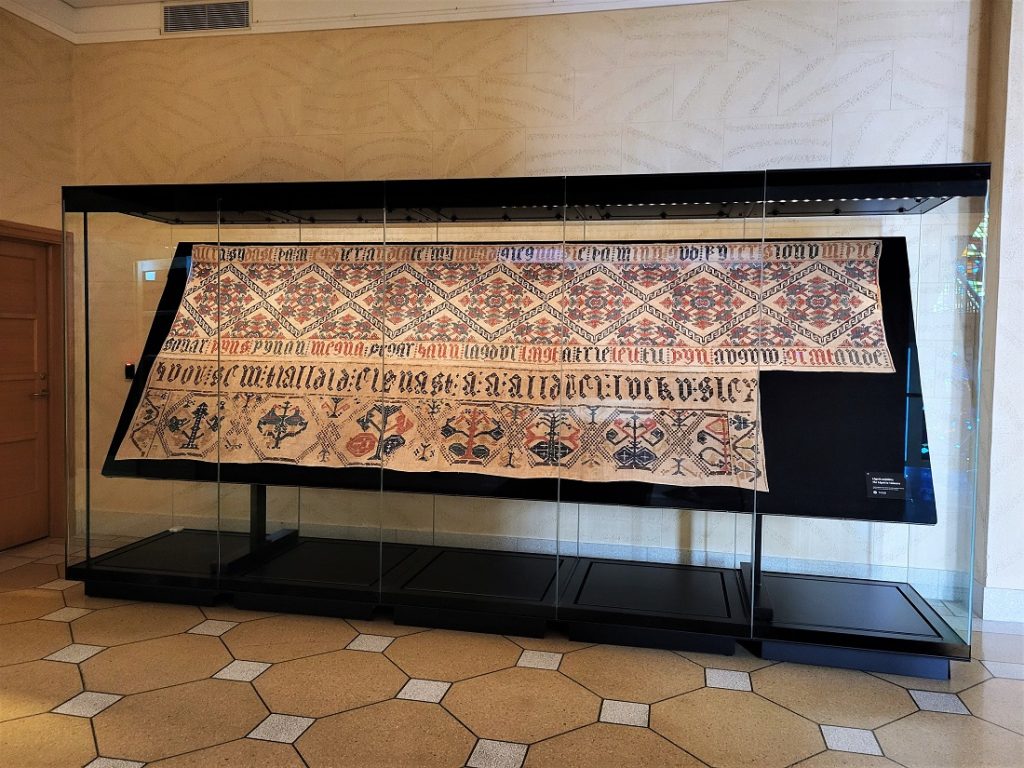

There was also a small, temporary display about the Lögrétta Valances (above), two Icelandic bed canopies that ended up in the hands of a Scottish merchant, Robert Mackay Smith, in the 19th century.

The canopies are now owned by the National Museum of Scotland and are on loan to its Icelandic counterpart for a year.

It was a curious exhibit and I enjoyed reading about this random connection between Scotland and Iceland.

From the temporary exhibits, I headed upstairs to the second floor where the ‘Making of a Nation’ exhibition culminates with a journey through the last 400 years of Icelandic history.

But just before I entered the main hall, I stopped to look around a small exhibition, ‘Capturing the Founding of the Republic in 1944’, which marked the 80th anniversary of Iceland’s independence (above).

The moving exhibit featured people’s recollections of the period, along with photos, videos and artefacts.

The second half of the ‘Making of a Nation’ exhibition explores absolutionism in Iceland, Reykjavik’s development, as well as the birth of the Icelandic nation and the development of modern life.

Other topics include traditional costumes, sailing and rowing (complete with a huge schooner in the middle of the gallery, above) and a traditional Icelandic turf house (below).

There was a lot to explore in this part of the museum and I really enjoyed learning about the more contemporary aspects of Iceland’s history and culture.

Of all the interesting objects on display, I was particularly taken by this beautiful 16th century drinking horn (above), which is intricately carved with scenes from the Bible, and I spent a fair while admiring it.

Overall, I enjoyed my visit to the National Museum of Iceland. The museum offers an interesting jaunt through Iceland’s history and culture.

It’s quite small, so it didn’t take long to look around and I saw everything in a couple of hours.

National Gallery of Iceland

Housed in an old ice house overlooking Tjörnin Lake, the National Gallery of Iceland was founded in 1884 and is the country’s foremost art museum, boasting some 15,000 artworks.

Set over three floors, the small gallery showcases 19th and 20th century works by Icelandic artists, as well as those by a few international names, such as Pablo Picasso and Edvard Munch.

When I visited in March, the gallery had a series of special exhibits to mark its 140th birthday.

I started my visit in the basement by looking around an exhibition featuring a host of modern artworks from the last century (above).

The gallery had a number of fun, eye-catching pieces, along with a few others that really weren’t to my taste (one was a graphic self-portrait by a female photographer in which she was peeing!?).

My favourite works included a collection of 12 plastic ants, The Conquering Army, which was created in 1988 by Magnús Tómasson (above).

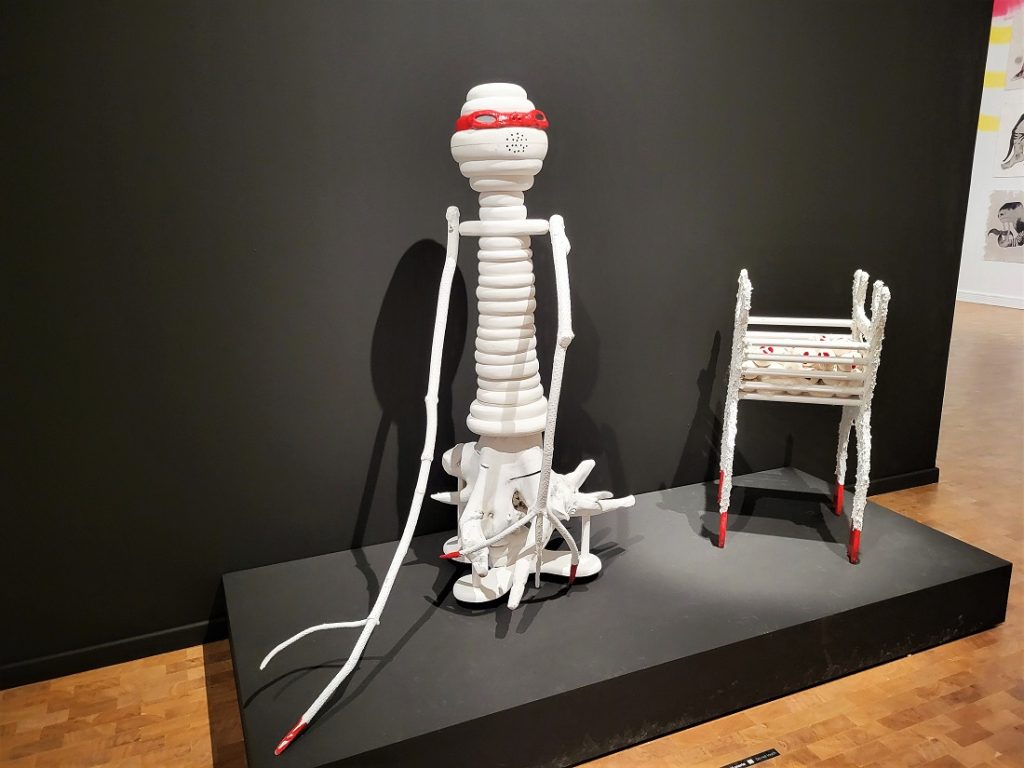

I also liked this quirky white creature next to a cot with distinctive red accents (above) – I have no idea what’s going on, but it made me smile!

I then walked up the stairs to the ground floor where I looked around a small exhibition dedicated to portraiture.

I love portraits, but I wasn’t wowed by many of those on display. I think they were a bit too modern for my tastes. Having said that, a few stood out to me – one was a self-portrait by Munch.

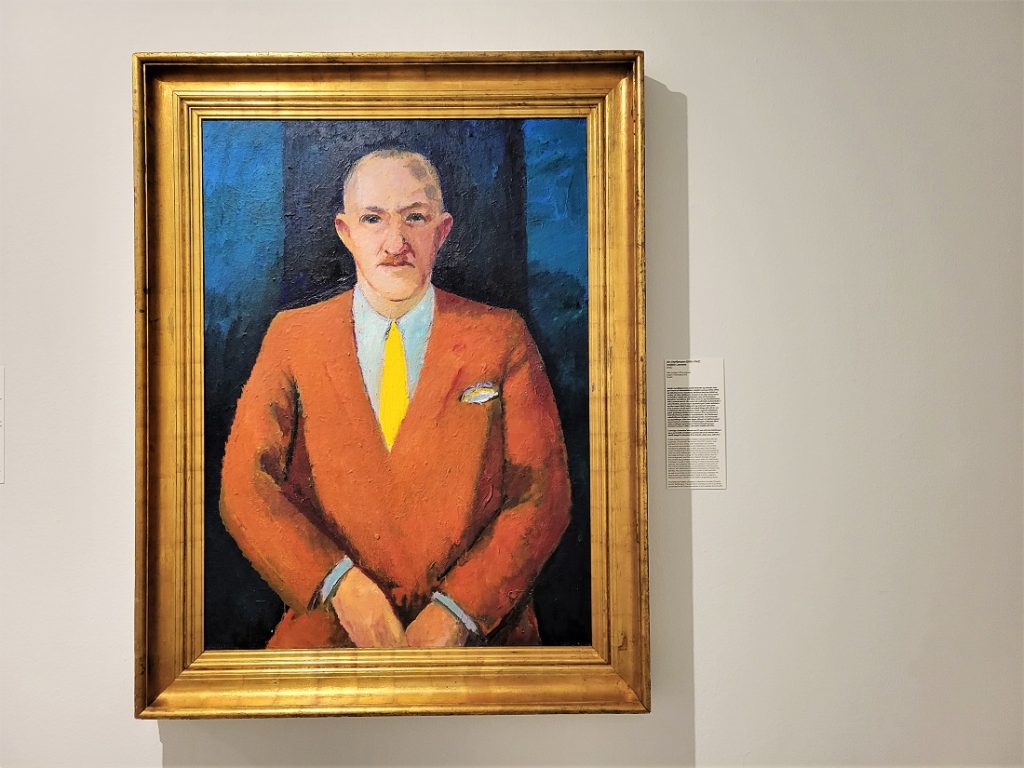

I also really liked Jon Stefansson’s striking portrait of Halldór Laxness (above), the Icelandic author who won the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1955.

I loved how the portrait combines bright, lively colours with the writer’s stately, dignified pose.

Anna Hallin’s ‘Women of Power’ (above), representing three female pioneers of Icelandic society, was another piece that caught my eye.

From the portrait gallery, I made my way to an exhibition on the first floor entitled ‘Intimacies of the Everyday’ (above), which showcased the works of five photographers.

Given its large size, the gallery felt pretty bare and the only photos I really liked were the colourful compositions by Scottish photographer Niall McDiarmid.

The final gallery was a bizarre and pointless exercise. It consisted of a huge bare room with a few plastic objects and some recycled panels.

I’m sure there was some deep meaning behind it, but there wasn’t really anything to look at and they could have just left the room blank for all the impact it had.

The National Gallery of Iceland was okay, but it didn’t blow me away. I liked the exhibitions for the museum’s 140th birthday, they were quirky and fun, but those on the top floor left me cold.

The gallery has a sister museum, The House of Collections, which you can visit for free with your ticket to the National Gallery.

Having found the national gallery a bit lacklustre, it wasn’t top of my list of things to see in Reykjavik and I didn’t have enough time to visit it.

Perlan Institute

Perched atop Reykjavik’s Öskjuhlíð Hill in a distinctive steel and glass building, you can’t miss the Perlan Institute.

Opened in 1991, the excellent museum explores Iceland’s natural phenomena, including volcanoes, glaciers, ice caves and the Aurora Borealis.

It’s set over six floors inside a specially designed building by Ingimundur Sveinsson, which consists of six heating tanks (they can hold as much as 4 million litres of water between them) topped with an enormous glass dome.

I started my tour in the ‘Forces of Nature’ exhibition, which focuses on geological phenomena, such as volcanoes, earthquakes, geysers and hot springs.

I then embarked on a journey through the history of Iceland, from 64 million years ago to the present day.

The detailed and interesting timeline covered all sorts, from Iceland’s formation through to how it was settled and the way in which geological events have shaped the country.

I moved onto a small exhibition inside a pod, ‘Mývatn: A Lake of Natural Wonders’ (above), which looks at the fauna and flora that live by the lake, including the Arctic fox, common loon and midges.

The pod transports visitors to Mývatn by playing birdsong, which I found weirdly soothing.

The ground floor is also home to a couple of other interactive displays:

- the slightly weird ‘Vibrant Birdlife of Látrabjarg Cliff’

- the informative ‘Our Underwater Community’ about the different species that live off Iceland’s coast, including the harbour seal, sperm whale and monkfish.

My favourite part of the museum was the ice cave (above).

This incredible 100m-long attraction recreates an ice cave, thanks to more than 350 tons of snow, and has the distinction of being the world’s first indoor ice cave.

It was unsurprisingly freezing inside (my toes took a while to warm up afterwards!).

But I had a whale of a time exploring the icy cave’s nooks and crannies, and it made for some incredible photos.

The only thing that spoiled it was a couple of young women who were holding their own photoshoot in the cave, barging in front of people as they were about to take a photo and blocking the tunnels while they took countless snaps of each other.

At the end of one mammoth photoshoot by the chair above, they didn’t even say thank you to the huge line of people patiently waiting for them to finish, although they made sure to thank each other.

It was staggeringly rude and entitled, and so obnoxious.

Emerging from the ice cave, I found myself in a superb exhibition about glaciers (above).

The exhibition is filled with thought-provoking, interactive features that teach people about Iceland’s glaciers and the terrifying impact climate change is having on them. It was excellent and I couldn’t fault it.

The last exhibition focused on water (above) and it, too, boasted clever, innovative features and activities, including tanks with pond snails and games about the creatures that live in Iceland’s waters.

It was really interesting and I learned a lot.

Having looked around the exhibitions, I made a brief pit stop at the café for the world’s biggest slab of cake and some tea (above), before heading to the ground floor as the Áróra display was about to start in the Planetarium.

The 22-minute show introduces visitors to the Northern Lights (handy, if like me, you weren’t lucky enough to see them) and explains their role in Norse mythology.

Photos and videos aren’t allowed once the show begins and there are warnings about what to do if you experience motion sickness.

The show was cool and I learned a lot (I hadn’t realised other planets such as Saturn also have their own aurora).

But I did occasionally feel a little queasy as I watched the screen swirl above me.

My final port of call was to the basement, where I watched a seven-minute show about the May 2021 Geldingadalir volcanic eruption.

The short film was fab and I couldn’t get over how close people got to the lava at the time – some people were literally standing next to it! It looked so dangerous.

I loved my visit to the Perlan Institute. It’s exceptionally well curated and a world-class museum, and by far and away my favourite of the three I visited in Reykjavik.

It’s a fantastic blend of fun, interactive displays and activities, and fascinating, well-researched information.

My brother, who’d been to Iceland a few years ago, had raved about the Perlan Institute in the run up to my trip and I can see why. It’s faultless and the best place I visited in Reykjavik.