Thanks to its bustling maze of a medina, traditional craftsmanship and stunning architecture, Fes offers a fascinating glimpse into Morocco’s long history and rich culture.

The oldest of Morocco’s four Imperial cities, Fes was founded in the 8th century, when successive kings established settlements on either side of the River Fes.

In the 11th century, the Almoravids merged the two into one and it became the Imperial capital in 1250 under the Merenid dynasty.

The city kept its capital status until the 17th century, when Moulay Ismail moved the capital to nearby Meknes.

The city then fell into decline until the French boosted its fortunes by building the Nouvelle Ville (New Town) in the early part of the 20th century.

Fes is now home to more than 1.2 million people and its medina was designated a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1981.

We started our tour at the Royal Palace, an enormous 200-acre complex in the Fes el-Jdid neighbourhood, which is also home to the city’s Jewish and Muslim quarters. There we met our guide for the day, Rachid.

You can’t go inside the palace because it belongs to the king, Mohammed VI, who visits a couple of times a year.

So we made do with admiring the palace’s stunning gates and its huge, beautiful brass-covered wooden doors (above).

From the palace, we drove to one of the hilltop forts overlooking the sprawling city to marvel at the panoramic views (above).

We then headed back towards the city centre, where Rachid tooks us inside the historic medina (below).

The bustling medina is made up of more than 9,000 narrow alleyways and it’s filled with shops and houses.

It was heaving with people and I’m glad we went with a guide because otherwise I would have gotten totally lost.

I followed Rachid through the medina in awe at my surroundings, regularly heeding to the cry of ‘Balak!’, the signal to get out of the way for an oncoming cart or mule.

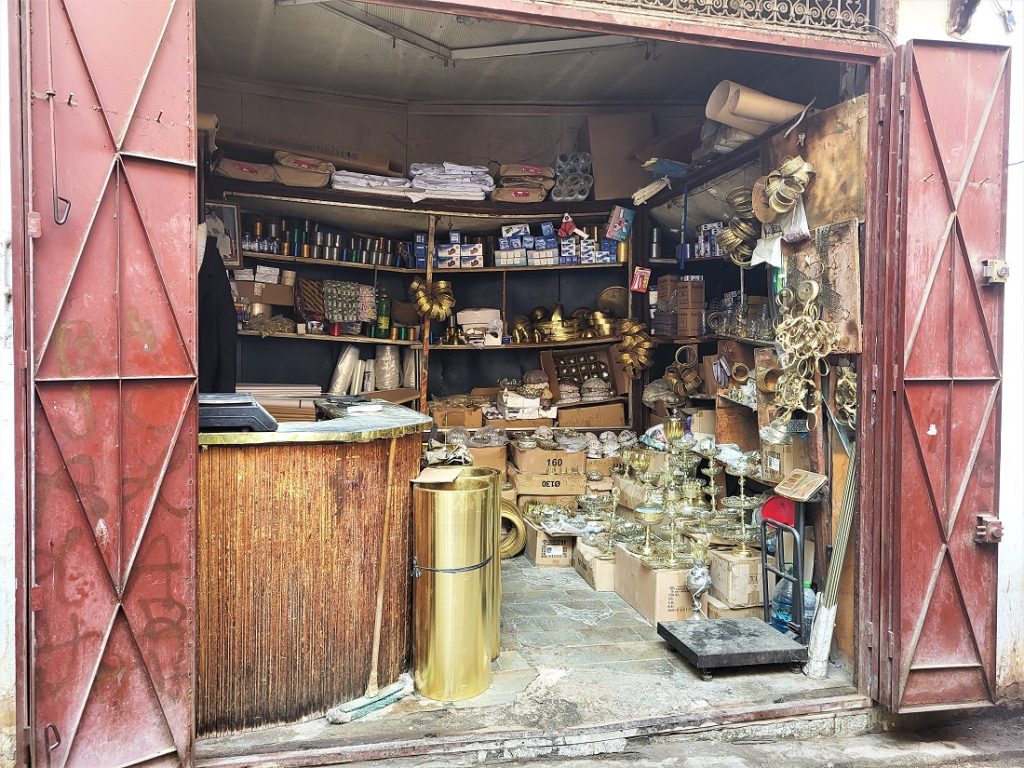

The stalls are grouped by trade, so all the brassware stores are together, as are the dyers, the leather goods and so on.

As we walked along the passageways, we could see the craftspeople at work.

I stopped to watch a blacksmith hammering away at something in the back of his workshop, while a couple of dyers showed us how they dye their silk threads.

It was cool getting a glimpse of how they make their wares and keep these old traditions alive.

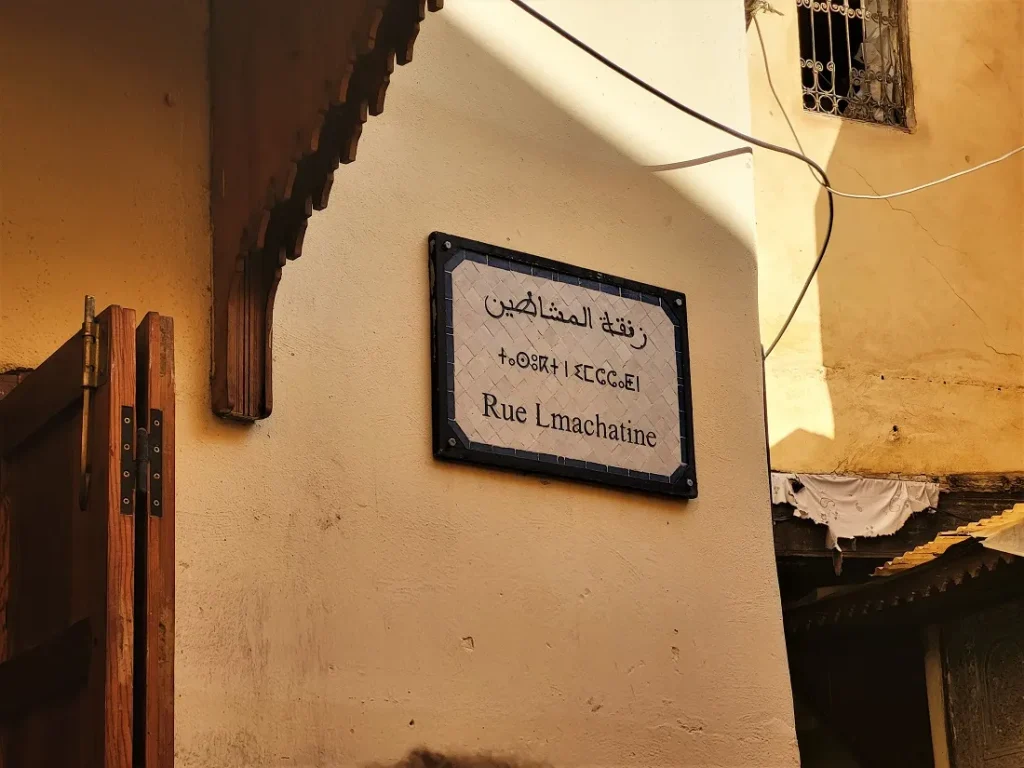

Rachid showed us how the medina’s signs give clues as to which way to go – a hexagon-shaped sign denotes a dead end, while a rectangle shows it leads to another alley (above).

We followed Rachid through the medina to a small marketplace where Moroccans can hire a middle man (usually an antiques dealer) to sell their goods on their behalf.

We then passed the silver and coppersmiths, stopping to watch as one man beat a copper pot into shape.

I had no idea where we were as we blindly followed Rachid through the intricate warren, and I quickly lost all sense of direction.

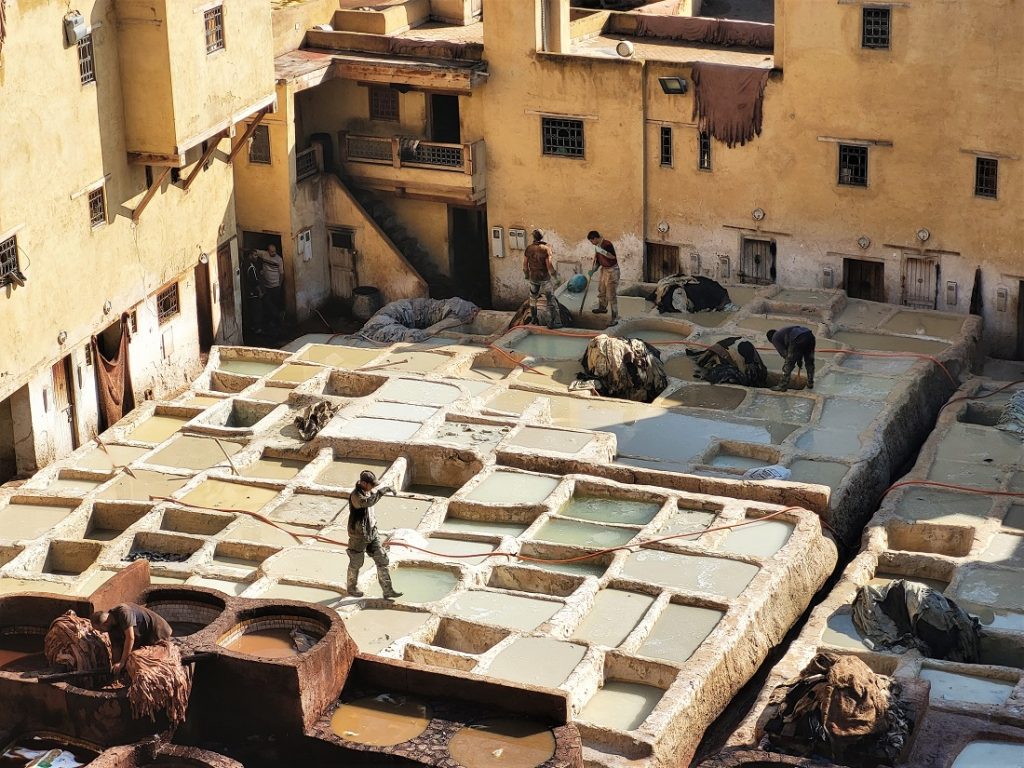

After a short while, we found ourselves outside a leather shop, where we were led up some flights of stairs to a leather cooperative and handed a sprig of mint “for the smell”.

The cooperative led to a balcony overlooking the tanneries, where a number of people were hard at work treating and dying animal hides to turn them into soft leather.

Some 50 families work in the tanneries, the craft being passed down the generations.

It was a remarkable sight, and a fascinating insight into one of the city’s traditions.

But it looked like back-breaking work, and I didn’t envy the people having to work in such tough, pungent conditions.

On leaving the cooperative, we continued on our way, passing a series of mosques and a beautiful 12th century fountain (above).

I found the noisy medina overwhelming. It was an assault on the senses – there was so much to see and the smells of the different trades wafted through the alleys.

We soon stopped at an 18th century mausoleum home to the tomb of Moulay Idriss (above), the founder of Fes.

Non-Muslims aren’t allowed inside, so we had to make do with a quick peek inside the ornate building.

Our next port of call was the fondouqs of Chemmaine (above) and Sbitriyne.

A few years ago, the fondouqs were in a dilapidated state, but they’ve been restored in recent years using money from UNESCO.

There were before and after photos of the fondouqs, and the work that’s taken place is astonishing.

They’re unrecognisable from the extremely sorry state they were in and it was hard to believe we were standing in the same place.

We kept moving through the medina until we reached the Karaouiyine Mosque (above).

Founded in 859, the enormous university-turned-mosque is thought to be the world’s oldest continuous university and its huge prayer hall can hold as many as 20,000 people.

Non-Muslims aren’t allowed inside. Instead we glanced inside an open gate, one of 14 entrances to the mosque. It looked lovely.

Next, we stopped at the El Attarine Medersa (above). The beautiful medersa dates back to the 1320s and can host up to 36 students.

We had a look around the large courtyard, which boasted a pretty fountain and some gorgeous tiles, and then popped into a small ornate room that led off from the courtyard (above).

We then climbed a narrow staircase to the side of the courtyard to take a look at the students’ sleeping quarters (above).

The warren of rooms was situated across two floors. While the central space was quite attractive, the rooms themselves were tiny and looked more like swish prison cells.

Our final stop was a weaver’s, where we were given a demonstration of how they make the delightful fabrics they turn into scarves and tablecloths.

The lively medina was a fascinating place and I was surprised to find I wasn’t hassled by anyone, possibly because I was with a guide.

It got pretty jammed near notable sites such as the Karaouiyine Mosque and the El Attarine Medersa (above), as lots of tour groups descended on them at the same time.

This meant there were crowds of locals and tour groups all vying to make their way down the very narrow passageways at the same time, causing utter chaos.

From the medina, we headed to a hilltop fort on the opposite side to the one we’d visited in the morning to see the city from the other side.

The view was incredible and it helped me appreciate just how big Fes and its medina are.

It was a much better vantage point than the earlier one and it was hard to miss the enormous Karaouiyine Mosque and its distinctive sea green roofs.

We drove down the hill to the beautiful Bab Bou Jeloud (above), where we stopped to admire its pretty tile work, before making our way back inside the medina to our hotel.

I was fascinated by Fes. It’s an extraordinary city and while I found the medina overwhelming, I enjoyed learning about the city’s traditions, its culture and its history.

The architecture’s spectacular, but it’s the tanneries and the opportunity to watch the city’s craftspeople at work that I’ll remember long after my visit.