On my second day in London, I headed into town bright and early to start the day with a little touristing. My destination? Westminster.

Situated on the banks of the River Thames in the heart of London, the historic district is home to a slew of the capital and the country’s most iconic landmarks, including the eponymous Westminster Abbey, Big Ben and the Houses of Parliament.

Inspired by the previous day’s visit to St Paul’s Cathedral, my first port of call was the magnificent Westminster Abbey.

The abbey, which has played host to countless royal weddings, funerals and coronations, dates back to 960 when it was founded by Benedictine monks. The current cathedral was built by King Henry III in the mid-13th century.

I’d visited the abbey years ago on a day trip to London with some school friends and hadn’t been back since, so I was keen to take another look.

But when I got there I found it was closed, so I had to make do with admiring it’s splendid exterior instead.

I wasn’t too bothered about not going inside as I was happy aimlessly wandering the streets and I can always go back another time – just, note to self and others, not on a Wednesday morning.

I strolled around the side of the cathedral to look at it from all angles. Then crossed the road at Parliament Square Garden, making my way past the Houses of Parliament and Big Ben, and over Westminster Bridge, where I stopped for a good look at the Palace of Westminster (below).

After crossing the bridge via the underpass, I headed back over the Thames, this time on the other side of the bridge, so I could take in the view to the east (below).

After admiring the Millennium Eye and the newly-restored Big Ben (below), I scooted around the side of Parliament Square Garden towards the lovely St James’s Park.

I don’t know why, but of all the parks in central London, I often forget about St James’s Park (below) and don’t visit it nearly as often as I should.

It’s a wonderful park and despite it’s central location, I don’t find it too busy – possibly because I’m not the only one who forgets about it.

I strolled through the park, stopping to take some photos from the picturesque bridge in the centre of the lake. Then meandered to the café, where I stopped for a warming hot chocolate.

Refreshed, I continued my stroll through St James’s to the enormous Waterstones on Piccadilly, where I browsed the many floors looking for Christmas presents, then crossed Lower Regent’s Street to the Japan Centre for sushi.

After lunch, I popped back to St Paul’s Cathedral to check out the crypt as I hadn’t had time to do so the day before and then made my way to the British Museum (below) to visit the Hieroglyphs: Unlocking Ancient Egypt exhibition.

Hieroglyphs: Unlocking Ancient Egypt is the latest blockbuster exhibition at the British Museum and it marks the 200th anniversary of the hieroglyphs’ decipherment by Jean-Fran?ois Champollion, a French Egyptologist.

The exhibition explores hieroglyphs, their use in Ancient Egypt, how they were eventually deciphered, as well as other forms of ancient writing.

Throughout the exhibition there are three ‘gem-birds’, based on the bird-like hieroglyph that means ‘to find’, to discover.

Each one gives visitors a chance to decipher a hieroglyph to learn an ancient Egyptian saying. It was a fun way to learn more about hieroglyphs and their meaning.

There are also lots of display panels that explain the meaning of different symbols – the owl symbol, for example, represents ‘m’.

The start of the exhibition focuses on early forms of writing, such as Coptic, and early attempts to decipher the hieroglyphs.

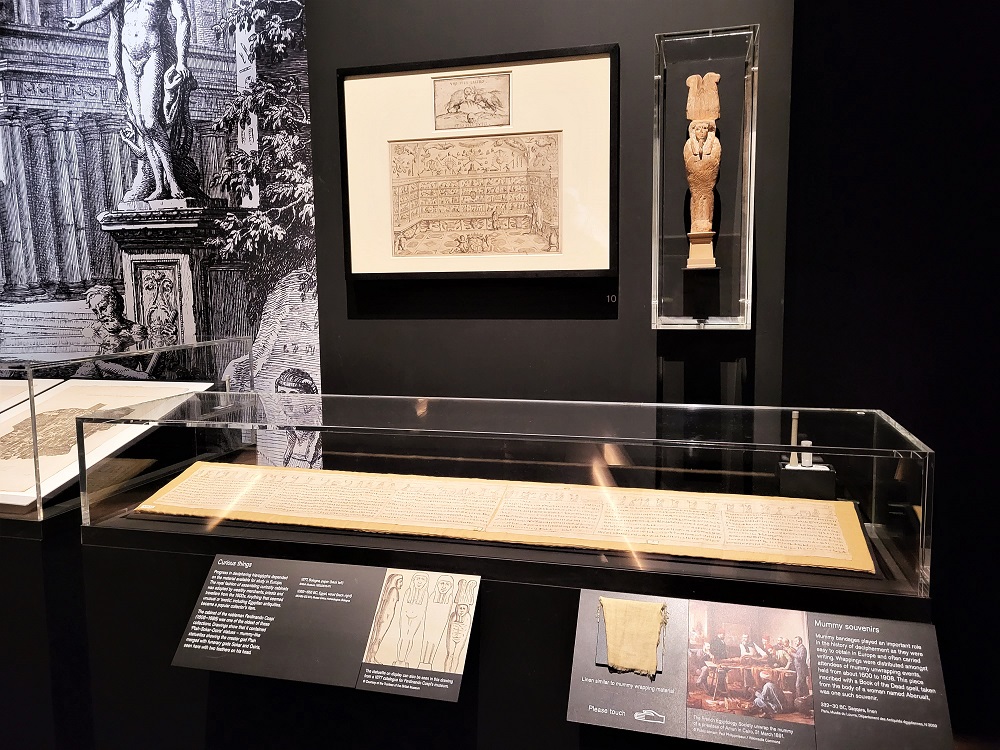

It also looks at the craze for collecting ancient Egyptian artifacts and the collections people amassed in previous centuries, many of which ended up in national museums, as well as the fake objects that inevitably cropped up.

Among the many intriguing artifacts on display in the early part of the exhibition is the ‘enchanted basin’, an ancient Egyptian sarcophagus dating from around 600BC, that’s inscribed with hieroglyphs (above).

One of the craziest and most macabre things I learned was that from the 1600s to the early 1900s people would have ‘mummy unwrapping parties’, where people would come together to unwrap mummified remains.

It’s such an inappropriately disrespectful, not to mention bizarre thing to do that it blows my mind that people not only used to think it was okay, but it was considered a form of entertainment. It’s like they didn’t view the individuals inside as human beings.

Many of the bandages had writing on them, so the unwrapped bandages proved useful to scholars trying to decipher the hieroglyphs.

The most notable artifact on display is the Rosetta Stone (above), the Memphis stele that was key to cracking the hieroglyphic code.

Its one of the most famous objects in the British Museum’s collection and has pride of place in the exhibition.

The celebrated stele was discovered by French soldiers in Rashid, Egypt in 1799 after Napoleon invaded the country and it was handed over to the British two years later as part of a peace treaty.

The stele features a decree by Ptolemy V, which is inscribed in three languages, one of which happens to be hieroglyphs, and it was this that helped scholars finally decipher their meaning.

A large part of the exhibition focuses on the ‘race to decipherment’ charting, in chronological order, the attempts of scholars at the beginning of the 19th century to decode the hieroglyphs.

Two scholars led the way, the aforementioned Jean-Fran?ois Champollion and the British polymath Thomas Young.

Scholars often relied on drawings that travellers visiting Egypt made of the objects they came across (above).

It was fascinating seeing and reading about the different objects and pieces of information that helped the scholars with their work.

Jean-Fran?ois Champollion eventually deciphered the hieroglyphs on the Rosetta Stone in September 1822, and he wrote about his breakthrough in a letter to his colleague Bon-Joseph Dacier (above).

The exhibition then moves on to look at how the ability to read ancient Egyptian texts has helped scholars improve our understanding of life in Ancient Egypt.

The many artifacts on display that helped with this included the Abydos King List (above), studied by Champollion, which lists the names of 34 Ancient Egyptian kings.

The Ancient Egyptians carved inscriptions or wrote on a variety of objects and it was interesting to see the range of inscribed artifacts, from statues of pharoahs (above) to cartonnages housing mummified remains (below).

But the exhibition also delves into the use of hieroglyphs in everyday life, from weights and measures to maths textbooks and letters detailing marriages, divorces and business deals.

So much of what we see and hear about Ancient Egypt focuses on the pharoahs, pyramids and mummified remains that it was interesting and refreshing to learn about everyday life in the kingdom and to see some of the objects they used (below).

I enjoyed Hieroglyphs: Unlocking Ancient Egypt. I really like codes and puzzles, although I’m terrible at solving them, and enjoyed having an opportunity to find out the story behind one of the most famous decipherments in history.

Info

Hieroglyphs: Unlocking Ancient Egypt

British Museum, Great Russell Street, London WC1B 3DG

£18

Open daily 10am to 5pm, 8.30pm on Fridays, until 19 February 2023